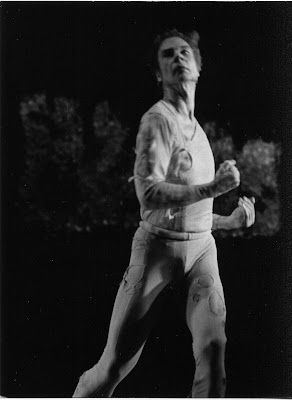

It was an absolute delight interviewing two amazing female filmmakers who captured an in-depth look at the development of a powerful, historic dance from the studio to the stage. Below is the transcript of my interview with Producer Lise Friedman and Producer and Director Maia Wechsler for their new film, IF THE DANCER DANCES which is about the re-creation of renowned choreographer Merce Cunningham's iconic dance RainForest featuring a set created by Andy Warhol and led by Stephen Petronio's dance company in New York.

Emily Clark: What attracted you to the project?

Lise Friedman: We had both seen the last performance of Merce's Company and we were talking about the fact that the company was going to disband two years after Merce's death which was his decision. I was a member of the company for many years...we started having an interesting series of conversations about the idea of how work does or doesn't live on once the choreographer is no longer in the picture--the ephemerality of the work--the fact that dance doesn't have a script or score and you can't go to a museum and see six decades of Merce's work on the wall. It has to be experienced in live time and has to be passed along from body to body, generation to generation...we were interested in the idea for a film. We went to approach the Cunningham Trust. We were interested to learn which pieces were being licensed around the world...it so happened that Stephen Petronio...had just licensed RainForest which... is one of Merce's most iconic and idiosyncratic and gorgeous works. We were fortunate in our timing and jumped at the opportunity and were able to capture the very first rehearsal all the way through performances at the Joyce Theater and beyond.

Maia Wechsler: Part of what intrigued Lise and myself...was that most people never thought to consider the difference between a work that vanishes and a work that remains. I talked to some sophisticated friends who would go to see dance and had never considered how a work exists on stage, how a work comes back to life... how a work is past from one cast or one generation to the next...we knew that if we focused on our characters we could draw in people who didn't feel any particular connection to dance...and they might feel a connection by being taken inside of this process and they would feel like they really knew something about dance.

Emily Clark: It almost felt like the camera wasn't there. Was that intentional as a director?

Maia Wechsler: We had two goals: One was to get as up close and personal as we could. The other was not to alienate our characters. We didn't want to be in their way. It wasn't easy for all of them to have us there...it was the first time that this work had been restaged after Cunningham's death and there was a lot of responsibility on everyone's shoulders. We were very sensitive to that. We did want to become a fly on the wall.

Emily Clark: Was there any reinvention involved in this recreation of RainForest? Did they feel that the goal was to precisely capture the original performance or to modify it?

Lise Friedman: That's one of the burning questions that comes up frequently when people start to talk about what it means to restage a piece. One of the great concerns of the stagers ... as you know from the film, we had three stagers... Andrea Weber was the one who had the most authority in the room. You sense her great anxiety and determination to be true to Merce's work, to be true to the piece. The idea was not to reinvent the wheel. The idea also was not to create an ossified version of the piece, to replicate it exactly as it was. Merce was always about dealing with the dancers who were in the room. No matter whether he was teaching a new work, or whether the dancer was learning a piece that was extant. He was always interested to see what a particular dancer would bring to that. The pieces would live and breathe and have particular nuance according to the dancers who were embodying the work. RainForest was restaged through a combination of the dancers, the stagers, all of whom had danced to the work most primarily through their own muscle memory, looking at some of Merce's notes, and working with other dances in the room, so there was a constant process of give and take. The Petronio dancers were doing the movement as it was given to them, but they were [also] given time to rehearse and to explore the movement and find their way into it. You see that process unfold in the studio.

Emily Clark: With no music, did the dancers comment on that or find it challenging to work with?

Maia Wechsler: Lise was accustomed to this and all the Cunningham dancers were very accustomed to working with no music. Merce is famous for working in silence and bringing in the music which was composed as a separate entity, in most cases, [and] only in performance. Clearly for an outsider like me, it was kind of surprising and I think it was surprising for the dancers as well. I think it was a little difficult for them. What's wonderful is when Rashaun Mitchell speaks about this very thing and how moving this was to him. I think there's something incredibly poetic about that silence, but I think it's hard to adapt to for newer dancers. This whole idea that Lise is talking about in terms of whether something is ossified...one of the things that we were eager to bring forward was this idea, this arc we called it, the arc of ownership. As we watch the dancers learn the steps, we understood in the film that it's not enough. They have to come into feeling like this work is their own, like they have a right to dance it, that they have something to bring to it. That's why we structured the film the way we did. It's not a typical dance film...we wanted to show the reality of the process which is that sense [that] dance ownership comes from performing the work and it's not [necessarily in] the first time and it might not be [in] the second or third, but it comes from this continuity of performing and performing. There's this time that the dancers need to make the work their own.

Lise Friedman: There's a moment in the film when Meg Harper, one of the stagers, says very poignantly that perhaps the transmission happens after we've left. It is a process and it takes time to find your way into a work. It is a process, it's not instantaneous.

Emily Clark: With your background in journalism, how did that aid you in documenting this particular film?

Maia Wechsler: I'm a documentary filmmaker, formerly a journalist, so the skill set that I developed as a reporter/writer helped me very much when I moved into documentary filmmaking, and yet it's a very different thing because filmmaking...is a really kinetic, movement-filled kind of process. I'm also a former dancer so I understand what it feels like to move. It was natural for me to come around to a dance topic even though I hadn't really considered it before Lise and I started having these conversations.

Emily Clark: What are some adjectives that you might use to describe Merce's work?

Lise Friedman: Intensely kinetic. Very emotive. Has a certain gravity. Linear, lyrical, antic, profound. I could go on and on and on. I have the deepest regard for Merce's work. Merce was a rare choreographer who could create work on bodies other than his own that didn't look like the movement was made on his [own] body. A lot of choreographers make work on other dancers that looks just like it would look on their body because that's what they're limited to. Merce had the capacity to make work with whomever was in front of him...very specific to their capabilities and [even] beyond their capabilities. Merce did away with story. It was a real change in dance form. The stripping away of story, coming into pure dance. A former dancer said," Merce never told us what to feel or what to think."

Maia Wechsler: What we saw is that there were dancers who wanted a little more information and that's our wonderful turning point. [When] the older black male dancer, Gus Solomons stops rehearsal, comes back and says, "you children are working so hard." He starts to give them some imagery in a way that we understand Merce rarely did and all the primary character stagers are paying special attention not to be too adjectival. But here's Gus, an older dancer [and] original cast member of RainForest, watching rehearsal and wanting to give these dancers something that will help them connect to the piece. He gives them this image of water and this image of sensuality. For some of the dancers in the room this was a pivotal moment for them to grasp onto something that they could relate to.

Lise Friedman: Even though he's giving them this wonderful insight and helping them find a way into the work through this imagery, he's not telling them what to feel or what to think. He's saying, "feel your environment, feel the water running down your skin." It was like a watershed moment for those dancers. They were struggling. There was a kind of strictness and unintentional limiting...it was incredibly interesting to watch that happen.

Emily Clark: In today's fast-paced society, we're very technologically driven. What do you think it is about dance that may help us connect with our humanity? And more specifically, why is Merce's work so important today?

Maia Wechsler: We're in the studio, everyone's stripped down to tights and leotards. There's a lot of touch, a lot of holding. It's tactile. Bodies are moving in space. Bodies meet bodies. As opposed to our distant, technological society, there are people in the room moving together, and there's a beautiful flow of humanity in that room. It's a real counterpoint to carrying on our lives at a great distance from one another.

Lise Friedman: In terms of Merce's point of view about movement, in this age where we are so fast-paced, where we are so technologically bombarded, Merce's work has always been about space, about time, about what he encounters in front of him, about a lived kinetic experience. Merce was very interested in blasting open traditional space. In his work with John Cage who was his lifetime partner and a composer, an artist, he was very interested in exploring the relationship between dance and music and visual arts. Merce is very much about...the immediate moment as well... he was a man ahead of his time.

Emily Clark: You were talking about the dance having its own vocabulary, what do you mean by that?

Lise Friedman: Merce has a technique that one can study. Technique are the steps--how you move, very much akin to ballet in that regard. The structure of Merce's classes are very similar to the structure of a ballet class. The departure comes in the style and the point of view of the movement and the use of the torso, the back and the feet. Merce had many different stylistic signatures. I would say that RainForest is one of the more idiosyncratic pieces. It's a chamber piece, for a small group with only six dancers. The movement is quite feral, incredibly sensual, very particular to each dance and A-typical; it's not like any other dance that he made.

Emily Clark: For future generations of kids that grow up and want to study dance, what do you hope for the future of Merce's work? What do you hope the audience will take away from this beautiful film that you've made?

Maia Wechsler: We hope people take away a deeper understanding of the process of dance making, of creation so that they feel a deeper access point to the art form. We wanted to expand the pleasure and the audience for dance. That was our ultimate goal in making the film.

Lise Friedman: We hope that we show situations that give young dancers a sense that there are entry points for them. There's a moment in the film where Davalois says, "I think I'm the first black woman to perform Merce's work professionally" and that's a big moment. Here's something a young dancer can understand. The other thing is that dance is a communicative art form. The body is an instrument, it's not something that's apart from you. We hope that young dancers, dance aficionados and people who are new to dance can experience the joy, the power, the rigor and the sheer artistry of it. For the future of Merce's work, we hope that dances will still continue to be significant... again, it has to be passed down from body to body, that's what gives it the authority. Otherwise it will become lost.

Comments

Post a Comment